Over the past few months I’ve learned that there is one person in my life who must be kept happy, or there will be hell to pay. His name is Col, and he is my colon. I think of him as my colon but he thinks of himself as a hard-working and loyal member of the team of organs in the Peritoneal Cavity. He’s not there for “Tracy” (whoever she is), but for the team.

Normally the organs of the peritoneal cavity are hidden from view, but once you’ve had part of your colon removed and the free end re-routed through the wall of the peritoneum, through fat, muscle and skin, to emerge into the outside world, then you get to see it. I had this surgery in 2014 during my first foray into the world of peritoneal cancer. It took two surgeons about six hours to excise my two abdominal tumours and as much of everything else they could take without actually killing the patient. They snipped the tube at the splenic flexure (upper left of the abdominal cavity) and at the sigmoid colon (the part just before the rectum) and put the snipped section in the bin1. They capped off the lower part of the tube, and brought the other end out at a point just to the left of my belly button. They folded it back on itself to form a stoma, a neat hole that would henceforth act as my anus.

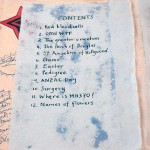

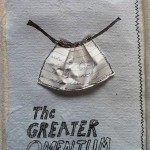

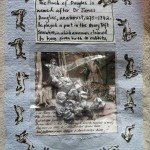

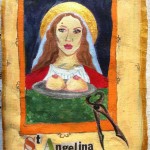

I have tried to imagine how Col felt about all this (see my new novel, The Vitals), but I guess I’ll never really know for sure. What is clear is that he has a commitment to his job, and performs it as well as he can, even under pressure.

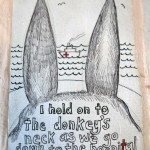

The problem with a shortened colon is that there is now less room for the results of over-indulgence. Sometimes Col just can’t keep things moving; I think he goes off for a nap to regain his strength. The result for me is increasing discomfort combined with increasing irritability. I do try to proceed normally, dealing with fellow humans and everyday activities, but all I really want to do is talk to Col: coaxing, cajoling, making promises (no more take-away Chinese sweet and sour pork with fried rice and dumplings) that I probably won’t keep. I’m not sure if he is listening or wants to listen. He has his own problems.

Anyway, today I’m glad to report that some sachets of Movicol eventually did the trick. Col cried relieved tears. Today I feel well and interested in the world again. There’s war and flood and Stage 3 tax cuts that are only going to benefit the wealthy, but there’s also two different colours of nasturtium (light and dark orange); velvety, blood-red geraniums; green tomatoes, a little forest of basil … all just a few steps from my back door.

If you know me or know some of my story, and if you’ve read this far, you may be interested in how I’m going. The question is always stated gravely, in italics. Fair enough. My situation warrants the gravity, the italics. The short answer is really well considering.

The “considering” includes the discovery of the return of cancer, this time in my lungs – nowhere else, just my lungs – followed by four rounds of chemotherapy between July and October 2023. This came after 8.5 years’ remission, as just as The Vitals was being launched into the world. The chemo cleaned up my lungs quite nicely. Within a few weeks, I’d stopped coughing and could breathe easily. I could walk uphill again without having to catch my breath. At the end of chemo, I was given “maintenance tablets”. Like chemo, these come with their own side effects, one of which is constipation (exasperated emoji).

These maintenance tables are very effective, particularly for people like me who have the BRCA1 gene mutation. Quick explanation2: When it’s working as it should, the BRCA1 gene gets in and restores the proper functioning of cells that are acting a bit weird. But a mutated BRCA1 gene doesn’t even see the weird-acting cells. This allows them to run riot at the back of the classroom, multiplying and creating tumours (I named mine Baby and Bunny in The Vitals). The maintenance tablets (called PARP inhibitors) work with the faulty mechanism of the mutated gene, making it even more faulty, causing the weird-acting cells to explode. (Maybe they don’t actually explode; maybe they just crumple into a corner and stop breathing.)

So, while it’s bad news that I have the BRCA1 mutation, I suddenly have an advantage over those with common-or-garden ovarian or peritoneal cancer not caused by the mutation (all the love and solidarity in the world to those in that position). It’s the beautiful result of years of scientific research. A fast-track to death is being replaced with lashings of hope. The tablets do not cure the cancer but they can hold it at bay for years, and possibly even indefinitely (it’s a new treatment, so not enough time has elapsed to check in on how things are going beyond about ten years).

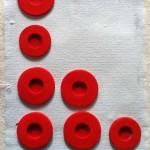

My own tablets, which go by the brand name Zejula, are eye-wateringly expensive. A month’s supply costs $9,874.39. Because we have Medicare, the cost to me is only $30, and the rest is covered by the taxpayer. Thank you Medicare. Thank you to the Whitlam government for introducing universal healthcare, and to voters who continue to support. (We live in a world in which cancer patients’ survival increasingly depends on success with pleas for money on sites like gofundme).

In Australia, the cost is a challenge to those who have to make decisions about how much we are willing or able to spend on expensive treatments that may or may not work. Medicare is not infinite; difficult decisions must be made. The drug is still under patent, meaning cheaper generic versions are not available. At the moment, in Australia, you can have subsidised Zejula for three years; after that, it’s a matter of waiting to see what happens. Of course, if you can afford nine thousand bucks a month, you’re laughing (as much as a person with metastatic cancer can laugh).

But how am I going? I guess the question is two pronged: what is actually happening, and how I’m feeling. It’s easy to explain what is happening but it’s harder to pin down how I feel. I can go from deep gloom to sunny optimism within a day (or an hour). Yes, there’s the ever-present sword of Damocles hanging over my head but the things that most affect my sense of wellbeing are the small-ticket items: constipation, sore throat, brain fog. At the moment I’m on top of the world because Col is happy. If Col is happy, I’m happy! “All ops normal”, as Col cries in The Vitals.

Next week, I’ll find out how well the Zejula is working for me. The big reveal will come by way of a CA125 blood test. If my tumour markers are stable or going down, brilliant. If they’re going up, not so good.

In the meantime, I’m making hay while the sun shines. I’ve already started writing my third novel. By “writing”, I mean percolating and thinking, not actual words on the (digital) page. But that’s okay, because I can feel the ideas taking hold of my hyperactive brain (“Queen Bee”) and running off with them in all directions.

- I’d always imagined a bin under the operating table for discarded body parts, but I’ve since learned that they keep a lot of them in the fridge, sometimes for a very long time. Col’s “lost” section could still be sitting in a vault at Westmead hospital. ↩︎

- I’m not a medical professional. This is how I understand it, and how I explain it to others. For expert knowledge, go to sites like this. ↩︎