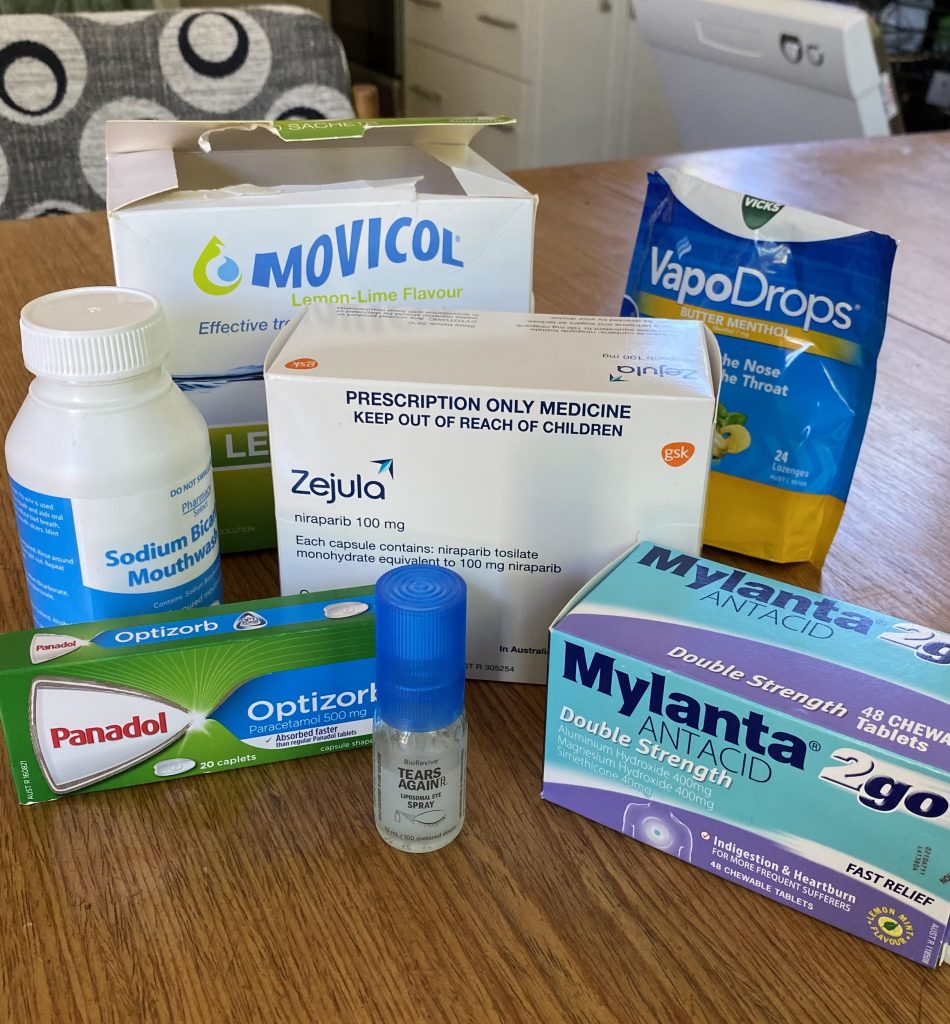

Spring continues to go bonkers, endlessly sending out shoots and growing giant green leaves. This is what I wrote last week at Varuna. Unhinged, unpolished … it’s the beginning of some sort of memoir-ish thing written as a series of short meditations on my various affected body parts. I’m starting with the Pouch of Douglas. This is one down; nine other body parts to go.

Illustration by William Hogarth, 1726. Retrieved from http://special.lib.gla.ac.uk/exhibns/month/aug2009.html on 23/10/14.

The Pouch of Douglas

The Pouch of Douglas is a small area in the female human body between the uterus and the rectum. It has a name and a shape but the essence of it, the point of it, is that it is a piece of nothing. It is a negative space. It is the empty air in a cup or a bottle. We don’t have a word for that territory; we let the vessel speak for it. The Pouch of Douglas has a name, a border, but no land. The territory of the Pouch of Douglas is infinitesimal, because when all is well the surrounding organs slide against each other like two slugs in a mating dance. The pouch of Douglas, like the pouch of a mother kangaroo or a coin purse, can expand to accommodate growing or multiplying things.

The pouch takes its name from the first man to explore and name this piece of true terra nullius. At the time, other men were planting flags in distant places on the globe; Dr Douglas worked closer to home in Scotland and England. He worked as a man-midwife, wrote treatises and held public dissections in his own house. Here is the uterus, the fallopian tube, the ovary and vagina. And here – can you see it? This is my own discovery. I have named it after myself. Ah, there is the bell for afternoon tea.

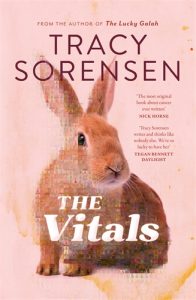

In 1726, a woman by the name of Mary Toft, who lived in Surrey, announced that she had given birth to baby rabbits. Her local doctor was astonished and ran off to let everyone know. She had been in normal labour, he said, with regular contractions. And then appeared the baby rabbits. The woman enjoyed her celebrity. But Dr Douglas smelled a rat. “A woman giving birth to a rabbit is as likely as a rabbit giving birth to a human child”, he said. He went to see her himself, to put an end to the nonsense. He examined her and declared her a fraud. Afterwards, William Hogarth made an etching of Dr Douglas standing at Mary Toft’s bedside, gesticulating, with the rabbit children running off in all directions, unmasked and embarrassed.

Rabbits came to Australia with the first fleet. Like currency lads and lasses, they grew healthy on fresh air and good eating. They eloped into the bush and ate the crops that were planted for them and built burrows in the new estates that opened up as far as the eye could see. Australia’s emblem bore the Kangaroo and Emu, but the continent was in fact governed by rabbits. The anti-rabbit wars, when they came, were conventional and chemical; mass slaughter and hand to hand combat. By the time I could walk and talk, I knew that rabbits had to be caught and killed. Even the family cat could do its bit. “Go and catch a rabby, Ginge,” my mother urged the big hard tom cat that went with the dairy farm my parents worked for a while.

That was in the south of Western Australia, where it was green and lush and muddy. That’s where my sister and I had the job of herding calves. We always stopped to examine the hot pats of manure. We noted that some were sloppy, some firm. We wore plastic galoshes. Dad was always hosing out the stalls where the cows had been. Mum grew tomatoes at the back door of the weatherboard soldier’s settlement cottage that we rented from the farmer. My parents had come from Queensland on a working holiday that was already stretching out towards a year. I started school at a one-room schoolhouse, where I open and shut my mouth pretending to chant the times table with my peers. Older children carried me around like a baby. We weren’t on that dairy farm for long. Winter was coming and these Queenslanders were drawn north, following the sun.

I believed in the Easter bunny. We were surrounded by rabbits, so the idea of a large one carrying chocolate eggs wasn’t too much of a stretch. I also had hard evidence. Before we left the dairy farm, Mum and Dad and my little sister and I were sitting together when we heard an interesting thump and scamper. “I think that was the Easter bunny,” said Dad. “Go and have a look in your room.” There, on the bed we shared with pillows at either end, where my feet would sometimes reach a cold wet patch that was my sister’s wee, were chocolate Easter eggs.

Carnarvon

Carnarvon was a place where red earth met white beach sand to create pinkish sand dunes sparsely covered in acacia scrub. There were utes piled high with kangaroo carcasses. There was the pub where Wilson Tuckey smacked an Aboriginal patron with coaxial cable and got fined forty dollars for assault. There was a NASA tracking station on the red sand dune just out of town, getting ready for the Moon Landing. And there were rabbits. We had a grey cat that dragged home a partly disemboweled rabbit. The rabbit was long, as long as the cat.

Running wild

My partner Steve walks over land near Bathurst, in New South Wales, that was box gum then eaten-out farmland and now a land care reserve. He stops at likely spots and takes co-ordinates with his pocket GPS. These are rabbit burrows. Rabbits eat the delicate native grasses being coaxed back onto the land. Someone else will come by, later, to gas the burrows. The rabbits will lie there, dead, under the ground. We go walking with our black Labrador, Bertie. Bertie is getting old and pretends not to see rabbits, because he can’t be bothered to give chase. Kangaroos stand stock-still as we approach. The full, hanging pouch with just the joey’s legs sticking out.

There’s something in my own pouch. Cells are multiplying, well-fed and happy, burrowing down in new estates. They’re going wild, like rabbits.

Nothing is a magnet for something

Dr Douglas named his pouch of nothing. Nothing is like a magnet for something. Nothing is a big blank page with a pencil beside it. Nothing can be a blessed relief. There is nothing there. I slide on my conveyor belt into the big white donut machine. The warmth of radioactive fluid is strange at the back of the neck and around the bladder. “Breathe in and hold.” Pause. “You may now breathe normally.” At this point I have never heard of Dr Douglas or Mary Toft or her baby rabbits. They belong to the new country on the other side of the donut.

Why did it occur to Mary Toft that she might gather baby rabbits and put them up herself? The vagina is an empty tube. It calls for something to go up it, into it. Perhaps she was bored, and she had an empty space to fill. And then she spied a baby rabbit.

“I’m bored,” I used to whine, back in the dairy farm days. “What can I do?” I would be told to go and find something for myself, and stop whining.

I took a hair from my head and asked Mum for a glass jar with a lid. I put the hair in the jar. I was thinking that this was the hair of today and today would not go on for ever, but I would always have this hair. I could trap a hair’s worth of time. The hair did not look impressive in the glass jar. In fact, it looked like an empty jar with a hair caught in it by mistake.

Was Mary’s first baby rabbit already dead, or did her attempt to birth it kill it? Did she practice on a series of rabbits, perfecting her fraudulent labour groans, the use of muscles for expulsion, before calling her local doctor?

There’s that name, Mary. And another highly unusual birth. I’m doodling, now, into the empty page.

Nothing asks for something. From nothing comes all of creation. We can’t seem to leave nothing alone.

The radiologist’s report described a five centimetre tumour in the Pouch of Douglas. And another bigger tumour, in another spot. I couldn’t listen to this. I let my friend Dawn, who had insisted on coming with me, take notes. Tell that other person that looks and sounds like me but is not me because that person belongs to another dimension. I need to stay here in my glass jar of time, in my ignorance, with other people opening and shutting their mouths like goldfish.

Gnashing teeth

The night before last I dreamed that Steve and I were talking to a woman, a stranger. She was about our age. She suddenly said she was miserable because no-one would marry her. Steve immediately offered to marry her. He said it the way he’d offer to help someone move bricks around to the side of the house.

As soon as he said these words, he was gone from me. He had shifted over, just like that. He’d made the offer, and now he had to follow through. I spent the rest of the dream wailing and gnashing my teeth.

Rabbits gnash their teeth at every meal with a wide side to side movement. Their teeth grow continuously through their lifetimes, to make up for the erosion.

You can know something, but if you don’t give it any words, it subsides into the mud. You can continue paddling about on the clear water above. You might even peer down through the clear water, to the bottom, but it’s just brown or gravelly down there, with water weeds growing out of it and tiny darting fish. So you continue paddling.

About a year before I started to feel unwell, I heard the word “cancer”, loud and clear, as I got out of bed. Just that one word, no more. “Silly”, I answered, and went on to do morning things. The word got short shrift. It shrank back and didn’t bother me again.

At night, though, I started downloading hospital books – one click of the Kindle – one after another. I read memoirs of doctors and nurses on the night shift, of surgeons performing the most delicate manoeuvres on aneurisms, of surgeons becoming ill themselves. I watched hospital shows on television. No fiction – they had to be the real thing. The more extreme the surgery, the better. I loved it when they cut holes in skulls to take out tumours, or transplanted livers.

I started to take long afternoon naps. In the middle of the day I would walk from my study to the kitchen for a cup of tea, only to be seduced by the sofa with its softness, its inviting rugs and cushions. I’d lie down gratefully and sleep. I began to do this even before lunch. I decided that this was the way I was grieving my father, who had died not long before. I was standing beside him, licking an ice-cream, and he was standing there in a striped shirt, holding a giant fish. Its nose was on his foot so it wouldn’t drag in the dirt, and his toes were curled up to keep it there. He held it by the narrow point just under the tail. The tail reached above my head. I was five years old, and we hadn’t been in Carnarvon for long. The black and white photo sits on a shelf beside the sofa. I gave myself permission to have the naps.

All this time, I was paddling furiously. I was teaching and marking and writing and I was editing a documentary. I’d spring up from my nap and land back at the screen, back at the keyboard.

All the cells in my body knew something, but they couldn’t reach my mind. “There’s no use trying to tell her,” they told each other. “She doesn’t listen.”

The wanted rabbit

Pongo the black and white rabbit was astonished when a giant cabbage appeared in front of him. He circled it a few times, wondering where to start. It was a round, tight cabbage. A rabbit has prehensile, grasping lips and strong incisors. A rabbit chews like a camel, with the bottom jaw going back and forth sideways.

Pongo is a wanted rabbit. He lives with his sister Mimi, a grey rabbit, and cousin Hester, a large, handsome hare. They live near the Bathurst railway station, a few streets away from us. When Mimi took ill, lying paralysed and hopeless on the floor, my friend Helen spent hours feeding her through an eyedropper and spent a ridiculous amount of money at the vet. Gradually, Mimi began to move again. She began to drag her body around. She’d tip sideways and be unable to get up. She’d be set gently back on her wobbly feet.

Mimi and I took ill at about the same time. We’re both still here. Our days are numbered, of course. We just don’t know how many numbers, how many days.

In the meantime, we continue to chew the many-layered cabbage of life. It is vast. It will be unfinished.

Rabbit victory

Ginge moves stealthily through grass, his belly close to the ground. He gives his hindquarters a tiny shake, springs through the air, brings down his prey. He closes his jaw around the neck, drags his prize home.

The boy sets off on foot, dragging a wooden crate on wheels taken from a baby’s pram. In the crate, a pile of steel-jawed rabbit traps. He pulls the jaws apart; they go as wide as they can go. In the dark, a rabbit sets foot on the lightly buried steel plate. The jaws slam shut, breaking leg and sinew. The rabbit screams. In the morning, the boy returns. The rabbit, exhausted, barely struggles. He pulls and twists the neck until it snaps. The rabbit’s soul ascends through the leaves of the gum tree into clear blue sky.

Back home, the boy skins and guts his rabbits in movements that are becoming fluid, habitual. The skins come off like gloves, all of a piece. He stretches them along the wire fence to sell to hatters. He carries the pink muscled rabbits, arms and legs stretched as if caught in the act of flying, in a damp hessian bag through the streets of Surry Hills and Redfern, shouting Rabbitoh! Rabbitoh!

The South Sydney football team was named after these men and boys, the rabbiters.

We settle in before the large screen. We don’t know who will win, the rabbits or the bulldogs. I still can’t follow a game of rugby league. It’s all about pumping thighs and tries. Red pumping blood andgreen, green grass, lit by electric light.

Victory. After 43 years, victory at last.

They taste it at Redfern Oval, then gorge. Weeks later, they’re still partying. Deb and I, walking down Pitt Street, hear chanting, slightly dangerous, coming from above. A Scottish voice behind us says, “There’s those fuckin’ Rabbitohs” – not disapprovingly. Partying Rabbitohs have become a feature of the streets of Sydney. They’re like Corellas, cockatoos of the desert plains, appearing unexpectedly in city trees, shrieking.

Ginge stands at the back door, offering up his rabbit. “Good boy Ginge! Thank you very much. But you have it, Ginge.” Ginge drags it behind the woodpile. The flesh is soft and bloody.

Rabbits are multiplying. Rabbits need lebensraum. Some must leave the Pouch of Douglas for opportunities elsewhere. It’s dark and wet and they can’t see where they’re going. They’re like baby kangaroos, blind and pink-skinned, groping their way towards the teats inside the pouch. Only this journey is in reverse. They must burrow upwards, as if towards the light, but there is no light, only another soft place to grow. They slip between organs, like a finger. They make room for themselves.

I can’t bear to look at it myself, but Dawn is reading aloud from the radiologist’s report. Steve is also unready to look at it himself. Dawn is our guide, like Virgil, into the first circle. After this she’ll go back to Canberra, back to her work as a nurse, and we will have to pick our way through this ourselves.

There is another tumour between stomach and liver, and it is eleven centimetres wide. It is not round with a definite skin, like an orange. It is more like a rabbit burrow, with a main room and corridors leading off it. It’s pushed the stomach right over to the left. It’s taken up residence. It’s a giant cuckoo in a small nest. It is growing rich on my blood supply.

I’m indisputably fading, now. My red blood cell count has plunged. My face is as white as a sheet. I’m bundled into a bed at Bathurst hospital, where they give me two bags of blood. I feel better immediately. Suddenly, I don’t feel ill at all. There are four women in the ward. One is ninety years old, estranged from all her children. There is nobody to bring her things.

Helen, mistress of rabbits, brings giant sunflowers. More flowers bank up. Vases have to be found.

I’m transferred straight from Bathurst to Westmead in Sydney. I sit in the passenger seat beside the driver, because I really don’t need the stretcher out the back. I’m perfectly ambulant, perfectly able to hoist myself up, click my own seatbelt. The nurse sits on a little chair behind my seat. She’s just a voice all the way down. I’m taken into the bowels of Westmead Hospital and fed a brown mushy casserole.

My sister, Deb, appears with an armful of new pajamas. She has written my name in felt pen on the tags at the neck, just as she does on her children’s clothes. Mum and Max are there too, and Steve. They are all gathered around my bed. Max is eight. He’s doing a crossword. He’s bored. I remember being six, a child at my grandfather’s hospital bed. We’d driven across the continent, Carnarvon to Brisbane, sleeping in the car, setting off at first light. Poppy was thin and smiling, telling stories. I picture him in a felt hat, but that can’t be right. He was in hospital.

A little while later, he died. Dad told me this, as we stood down near the road at the front of the small green fibro house that went with his job at Jolly’s Tyre Service. “Did you cry?” I asked. I looked up at his face. If he had cried, there was no sign of it now.

The fleece

We are like the girl in the rhyme

calling where o where,

hands deep in the fleece of ourselves,

wanting someone

with verbena-scented hair

and fine-boned wrists

to lift us up, the whole of us

containable, not yet broken.

– Maya Janson, Murmur & Crush

My hand is deep in the fleece of my life. My sheep are dirty cream or light brown, never white. In the angled light of the late afternoon, they are golden.

We took the ferry to Stradbroke Island and discreetly sprinkled his ashes here and there. Mum and Dad met on the beach here. They would forever have beach sand between their toes. I stood knee deep in the water holding the big plastic container in my hands. It was light grey or blue, with a lid that was very hard to get off. It was a purely functional vessel, of the kind that might contain fertiliser or snail pellets at a hardware store. Despite all our sprinklings, the container was still heavy. The coffin was in there too, diluting and adding weight to his ashes. We would have to stop sprinkling and start pouring, if we were to get this job done. The ashes rolled in the shallow water of Moreton Bay.

The drawbridge came down and we drove into the maw of the Argo, one down but not broken, and returned across the water.