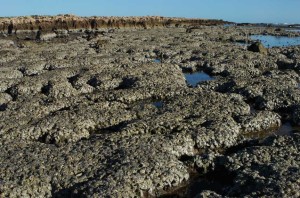

At the Blowholes, a popular fishing and camping spot north of Carnarvon in WA, there’s a sign that says: “Yes, you may eat the oysters.” I’m assuming it’s still there – it was in 2005 when I took Steve to see one of my favourite places on the planet. At first it looked like one of those signs that give you a great big list of things you can’t do. But this one just said go for it, and gave hints and tips. Prise the shell open with a bread knife. Swish the oyster round in the sea to rinse it. Chew and swallow it, savouring the blast of pure ocean feeling. Or something along those lines.

Today I’m thinking about oysters and impermanence. Last week, it was a year since Dad “went”. I like that euphemism. He went somewhere, not sure where, but the fact is that he is gone and isn’t coming back. Not the way we knew him. I think of his arm muscles. He used to pump them up to show them off. The blood coursing through those veins. The tattoo on his bicep with the pink love-heart and the word “Yvonne” in a scroll across it. Just before he went, I looked at that tattoo, so familiar all my life, and noticed that it was hanging on loose skin and you could no longer really tell what it was. That was once the strong arm that changed tyres, drove trucks, prised oysters out of their shells from the rocks.

Nothing (nothing that we definitely know about) is permanent. Everything is coming and going, coming and going, coming back in different form, from a living body to ash to a living body again. There is no permanence, but there can be repetition.* You can’t go back to how it was, but you can do things again. It won’t be like the last time but it’ll remind you of the last time. You can eat oysters again. That’s what we did last Wednesday when, in honour of Dad, we bought a towering stack of seafood at the Shelly Beach golf club, with a view out over the sea, this time the Pacific. Most of the seafood, I’m sorry to say, was pretty ordinary. There is nothing like growing up on the coast of WA to spoil you forever for fresh prawns and lobsters (we called them crayfish or crays). But the fresh oysters, served in their shells, were plump and the taste was not nostalgic but thrillingly right-now. The oysters of now!

I can’t go back and eat the oysters of then. But I can eat the oysters of now. Dad is, all at once, a boy and a man and some ashes floating in Moreton Bay between the mainland and Stradbroke Island.

We’re all coming and going. We’re the bored child at the bed of the ailing relative, and we’re the ailing relative. We’re leaping through a sprinkler and we’re painfully making our way down a hospital corridor, drip-stand in tow, heading for the light coming through the window.

Just after my surgery in May, my friend Jacquie brought in a book of quotes by Jack Kerouac called You’re a Genius All The Time. After she’d left, I sat in bed and read:

No fear or shame in the dignity of your experience, language & knowledge

We’re all coming and going, all the time. Death is the primary fact of life; it’s there in life’s first breath. And yet there’s this fear and shame. Being diagnosed with Stage 3 cancer has sometimes felt shameful, even though I tell myself there’s no shame in it. I’m somehow failing, not doing life right, by growing tumours in my abdomen. And yet this is ridiculous. Everybody dies; everyone who has ever lived has died or will die. There is no shame in growing tumours or having tuberculosis or a stroke or a heart attack. These are simply different forms taken by the great, inevitable, unavoidable fact of life.

Reading that sentence from Kerouac, I sat in bed sobbing, but in a good way. The young nurse got interested. “Who is Jack Kerouac? I’ve never heard of him.”

“He wrote a book called On the Road.” I think she thought Kerouac was some sort of self-help author.

“What does he say?”

I read out the sentence, sobbing through it again.

“That’s true,” she said.

Today, I feel good and most excellently alive. All my numbers and scans are excellent. My tumours have been taken out. The doctors are impressed with my progress. I have only one more chemo session before the end of all this treatment and surgery. After that, I can look forward to feeling well in Spring. And then I can look forward to a nice long remission. Let’s say twenty years – why not? Every now and then, during that time, I’ll eat oysters.

* Repetition is the only form of permanence that Nature can achieve.

wonderful Tracy – connoisseur of oysters of now.

thanks for sharing this lovely celebration of your dad’s life

Jack Kerouac was one of the great influences on my early life. I lived the life of a dharma bum as he did for years, until I realised that I was going nowhere. He was an alcoholic, but could write like a dream.

Alan Watts was another California guru (who was also an alcoholic – what’s with these guys?!), a Zen Buddhist who could also write up a storm. He once wrote:

“Suppressing the fear of death makes it all the stronger. The point is only to know, beyond any shadow of doubt, that “I” and all other “things” now present will vanish, until this knowledge compels you to release them – to know it now as surely as if you had just fallen off the rim of the Grand Canyon. Indeed you were kicked off the edge of a precipice when you were born, and it’s no help to cling to the rocks falling with you. If you are afraid of death, be afraid. The point is to get with it, to let it take over – fear, ghosts, pains, transience, dissolution, and all. And then comes the hitherto unbelievable surprise; you don’t die because you were never born. You had just forgotten who you are.”

I know that statement can also be filed under “weird, man”. But Trace, it seems like you’ve really been kicked over the edge of the precipice and come through scarred, sane and immensely wiser.

I am pathetically grateful that you have survived this experience. Whatever comes next will be a wonderful bonus, one that that you richly deserve.

We all know this, somehow, but still we choose to forget it, ignore it, wish it away, try to outfox it. Death will come, but how we live is the point of the thing. Tracy, you’re a top example of living it well, and reminding us that fighting is an option. Good on ya!

Wonderful philosophy Tracy.

I have just read a very moving book by Andrei Makine , virtually on permanence and impermanence, called “Brief Loves That Live Forever”. (I would send it to you if you have not read it except I got it on Kindle.) It says a lot but is a short and easy read except for the mopping up of tears.

I am sure you would like it.

Wow! Love your words! So deep, don’t often read, think, delve into deep feelings and tear up simultaneously and still manage to feel positive at the end very often! You have a true gift! Thank you!

Those tumours were no match for you! Or Steve! His challenge was also huge but you have both prevailed magnificently. Unfortunately no other oyster will ever match a Blows oyster and I agree with Barry: Everyone needs to have Dharma Bums on their reading list.

Megan said it for me. So much that was so familiar, though I never developed a taste for the oysters leaping up at me from the nambucca river. The blog just gets better and better. Hoping you will too. Jx

Yes, the oysters and all things seafood from those times were incredible. It’s so strange (or maybe not?) that I thought of asking you and Deb about your memories of Brian’s tattoo just hours before I read your blog! Keep up the good work of sharing your experiences – so inspiring! xxMum.

Trace. I told you I loved the way you wrote about the seamstress cutting through cloth. And I do. It has always been my favorite group of words. Until now. ‘ You may eat oysters’ is sheer brilliance and warms me (even in Canberra) x

http://www.dailymail.co.uk/health/article-2676288/Stunning-Crohns-sufferer-pursue-dreams-model-bikini-photo-exposing-colostomy-bags-internet-sensation.html

Great news!