Ah, the road trip. Watching the world change as the miles fall away behind us. Crispy yellow grass and golden wheat giving way to light green and deeper green as we reach the bottom of Victoria. Sheep look whiter. Black and white cows gleam. Along the side of the road, a thin strip of bush, a shadow of what was there before. It’s starting to rain. Birds are standing carelessly on the road, barely bothering to get away from the cars and trucks. What’s wrong with these birds? Oh look, they’re drinking. It’s been dry, and now it’s wet and the bitumen road has dips where water can gather. We drive into a violent storm, a watery world, visibility so low we have to stop. The sun comes out, we move on, and there are branches and leaves all over the ground.

Ah, the road trip. Watching the world change as the miles fall away behind us. Crispy yellow grass and golden wheat giving way to light green and deeper green as we reach the bottom of Victoria. Sheep look whiter. Black and white cows gleam. Along the side of the road, a thin strip of bush, a shadow of what was there before. It’s starting to rain. Birds are standing carelessly on the road, barely bothering to get away from the cars and trucks. What’s wrong with these birds? Oh look, they’re drinking. It’s been dry, and now it’s wet and the bitumen road has dips where water can gather. We drive into a violent storm, a watery world, visibility so low we have to stop. The sun comes out, we move on, and there are branches and leaves all over the ground.

No more sheep, just cows, now, and a landscape that feels so familiar to the European peasant lurking within the DNA. Gently undulating hills and cows, just like the picture on the tins of coloured pencils in primary school.

Near Timboon, we whizz past a grey shape on the side of the road, among the leaves. “It looks like a koala!” Ranger Steve immediately slows the car, checks the rearview mirror and puts the car in reverse. We drive backwards for a long time, until we come level with grey body. It is, indeed, a koala. We get out to inspect and pay our respects. This is a beautiful koala, a little bloody but all in one piece. There are those big, fuzzy ears, the black nose, the delightful roundness of the belly. He has neat, egg-shaped testes and slim curved back legs. His hands are large and leathery and expressive. Steve presses down on the fur. The body is stiffening but still gives. The death was not too long ago. He lived in the thin strip of gum trees along the side of the road. He could roam north or south but not east or west. Beyond the thin strip of eucalypts, the gleaming green dairy paddocks.

Later, we hear that the young cricketer Phillip Hughes has been hit in the head by a cricket ball. There is a vigil by his bedside.

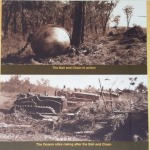

It’s dairy country, so we go looking for cheese. At the Apostle Whey cheese factory the husband is behind glass working on the cheese. He is on display. He is all in white, like a lab worker, with a gathered white hat like a shower cap. He takes plastic containers of lumps of white stuff, jiggles and pours. The wife is behind the counter, giving us tiny squares of the various cheeses. We buy the blue cheese and the smeared Havarti. On the wall, a row of pictures traces the history of the dairy industry in these parts. They cleared the bush with a giant ball and chain, dragging them across the land, pulling trees out by the roots. This was no nineteenth pioneer activity, with men attacking trees one by one. This was industrial-scale clearing in the 1950s, after the war. Gum trees and koalas gave way to pencil-box scenes of green grass and cows.

It’s dairy country, so we go looking for cheese. At the Apostle Whey cheese factory the husband is behind glass working on the cheese. He is on display. He is all in white, like a lab worker, with a gathered white hat like a shower cap. He takes plastic containers of lumps of white stuff, jiggles and pours. The wife is behind the counter, giving us tiny squares of the various cheeses. We buy the blue cheese and the smeared Havarti. On the wall, a row of pictures traces the history of the dairy industry in these parts. They cleared the bush with a giant ball and chain, dragging them across the land, pulling trees out by the roots. This was no nineteenth pioneer activity, with men attacking trees one by one. This was industrial-scale clearing in the 1950s, after the war. Gum trees and koalas gave way to pencil-box scenes of green grass and cows.

We reach the Southern Ocean. The sea has taken great bites out of the soft rock, leaving uneaten bits to dissolve in the mouth. These chunks of rock, the sea curling at their feet, are horizontally striped, showing off layers of time. Birds flit over them. These are starlings. The waves crash and foam, crash and foam.

We reach the Southern Ocean. The sea has taken great bites out of the soft rock, leaving uneaten bits to dissolve in the mouth. These chunks of rock, the sea curling at their feet, are horizontally striped, showing off layers of time. Birds flit over them. These are starlings. The waves crash and foam, crash and foam.

Phillip Hughes has died. This is shocking. Like the koala, he is too young, too perfect a specimen; he has barely begun.

UPDATE: We’re now camping at Blanket Bay in the Great Otways National Park. On the way in we saw no fewer than three koalas in the trees. Two asleep, one happily munching on leaves.

Have a wonderful touring around. Still love your blogs. Can’t wait till Thursday’s to see what adventures you have had for the week. We are in Bali having a wonderful time. Love to you both xxx

The clearing of WA’s South West was also on an industrial scale. A million acres cleared every year was the declared intention and they probably achieved it as the machinery towed giant ball-and-chain through the bush.

It began after WWI. The returning soldiers were surly and rebellious. They led the strike on the Fremantle docks in 1919 during which the police beat a young man to death – after having sprayed the docks with machine gun fire to force the occupying wharfies into the streets.

The Communist Party formed out of that and other waves of militancy, led by Hugo Throssell, who had won the VC at Gallipoli. The government determined to separate the returned soldiers from the Communists and turn them into stalwart Aussie battler farmers, in the spirit of the British yeomanry that loyally served the Empire in massacre after massacre.

So, the south west was cleared. The soldier settlers went broke or were driven mad by the Great Depression and their farms were bought out by wealthier neighbours.

Empire, violence, madness and war; war on humans, war on the environment capped by monopolisation. The origins of WA’s wheat belt are largely forgotten today. But the rising salinity is eating away at the very foundations of the towns.

Evocative writing Tracy. Thank you.

I hope there are no more sad discoveries on the rest of your trip. Enjoy it.

You’re drawing nearer! Looking forward to seeing you on the weekend. Phil Hughes and I were both born in Macksville…That’s where our commonality begins and ends. I was only a figure of fun for Pete and Bernie’s boys when I got behind a cricket bat. I laughed along. My nieces put their cricket bat out by the front door this week.