I’ve just had a flying visit from my friend John Merkel who is heading back to Melbourne tomorrow. He’s loving Melbourne and his new girlfriend and generally getting about being a Lebenskünstler. After I showed him my crocheted guts, he got his iPhone 3 out of his pocket and asked if I’d mind repeating myself for the movie. I said I didn’t mind. It’s worked out well, actually, because I was beginning to wonder what I was going to blog about today. As you can see from this clip, my eyebrows have come back nicely.

Tag Archives: primary peritoneal cancer

Whipping up a sponge

So, what now? Last Friday at about this time I was getting the cannula out after my final blast of carboplatin and taxol. Saturday and Sunday were steroid days. On Saturday I pruned ivy and carted piles of it out the back in the wheelbarrow, clearing bricks down the side of the shed along the way. That’s what steroids can do for you. On Sunday, my friend Dawn, who happens to be a nurse, drove up from Canberra to see me through my post-steroid crash on Monday and Tuesday. Only this time there wasn’t a crash. She came up with a novel idea: eat pain killers and anti-nausea tablets before the pain and nausea. Get in first, don’t wait until it all hits before you try to zap it. Seems obvious now, but it’s not how I’d been playing it. I’d be laid out on the couch, staring at the ceiling, enduring the day somehow and thinking, “I’d better take some tablets”. So this time I lined up the pills and ate all of them before the steroids even wore off. The next morning the oncoming train switched over to a set of parallel tracks; all I felt was the buffeting of the air as it went past. So I got through my bad days without feeling particularly bad. I’d expected to finish off my last chemo session with one last great wipe-out finale; it ended with a whimper. A wonderful whimper.

So, what happens now? I have been waiting for, yearning for, this moment. Treatment is finished. I don’t have to cower before the thought of the next chemo. I do have to go back for a CT scan on August 20, which will show whether the cancer has entirely vanished or if it has left a bit of itself lurking somewhere deep and hard to get at. And there’ll be endless follow-up tests. But right now, I believe it’s perfectly reasonable for me to celebrating the end of whatever the hell this last seven months was all about. FINISHED. HOOORAAAAAY!

But now what? My problem now is that I feel I’ve been given a life, a life that was looking horribly endangered just a few months ago, and I’m all at sea. Last birthday, Mum gave me a black and white photo of me as a baby, all plump with a great big white nappy. She also gave me one of the pink safety pins – a little rusted now – that held my nappies up. In the photo I’m bald and have a slightly baffled look on my face. I feel I’m back there – bald, baffled, now wearing a colostomy bag rather than a nappy. I’ve been given this new body, and the luxury of time. What do I with these things?

I don’t know. In the meantime I’m continuing to crochet as though my life depended on it. The crisis is over, but the granny squares are still piling up around me. I finish one and start on another, like a chain smoker. With all my new insights and experiences, I feel I should be living life on some sort of higher plane. I shouldn’t be wasting time. I should be living every moment in honour of the miracle of life. Which means I should be doing … what, exactly?

One option – just for today – is to leave everything exactly as it is. It’s okay to crochet. It’s okay to be baffled.

Meanwhile, Dawn is whipping up a sponge. I can leave Dawn to do the meaningful and life-changing thing today. This lets me off the hook (not the crochet hook, nothing is getting me off that). It’s well known among Dawn’s nearest and dearest that she’s not the most interested or skilled cook in the world. So the idea of Dawn whipping up a sponge has been a long-running joke. About a year ago, she said she’d actually do it one day just to surprise everyone’s socks off. She’d practice a few times and then say, casually, “Oh, I’ll just whip up a sponge” and then follow through. On Tuesday, when I was feeling unexpectedly not too bad, we went to the supermarket and bought all the things for a sponge, including a round sponge tin. But we forgot the caster sugar, and it felt too hard to go back out and get it, and in the end we didn’t do it. It was hard to watch her drive away, spongeless. But she promised to do it today (Thursday). I was dubious. Would she really follow through and make the sponge without me standing over her?

I think I was so interested in Dawn’s sponge because for her to make one is so out of character as to count as a major life event. She’s always been active in causes and committees and volunteer work – doing good in the world – but somewhat neglectful of the sponge-like little things in life. Somehow, if Dawn could make a sponge it would show that it’s possible to be different, even if just a little bit.

Anyway, today, Thursday, Dawn whipped up a sponge. She texted me a photo. She baked two sponges, so that one could be set upon the other and they could be joined together with strawberries and cream. The photo shows two flat objects. They didn’t rise. But I don’t care! She did it! I’m ridiculously pleased. I don’t know what to do with myself but it doesn’t matter, because Dawn has whipped up a sponge.

Anyway, today, Thursday, Dawn whipped up a sponge. She texted me a photo. She baked two sponges, so that one could be set upon the other and they could be joined together with strawberries and cream. The photo shows two flat objects. They didn’t rise. But I don’t care! She did it! I’m ridiculously pleased. I don’t know what to do with myself but it doesn’t matter, because Dawn has whipped up a sponge.

What about the last guy?

Today I’ve been talking to a journalist from the Sunday Telegraph. She’s doing a series of stories about the extra challenges faced by cancer patients who live in the bush. She found this blog and gave me a call. I think it’s great the Tele is doing these stories. In New South Wales, the further away from Sydney you live, the more likely you are to die from your particular cancer. If you don’t have a car, live in a small town with little or no public transport, if you have poor literacy skills or no Internet access … even if you simply have problems keeping track of appointments, your outlook can start to dip. For those needing to travel to Sydney for treatment, the whole business of organising and paying for transport and accommodation can be overwhelming. Some simply give up. This is an issue that needs airing. In a rich country like this, cancer survival rates shouldn’t be so affected by one’s address.

For me, though, distance has not been such a tyranny. I have a partner able to take time off work to drive me back and forth and a friend in Newtown offering not just the front room but delicious dinners (and the company of two gorgeous kelpies). I have, though, often wondered how well I’d be coping if even one or two pieces of my support jigsaw were missing.

Anyway, it’s all making me think of Arlo Guthrie (son of Woody) talking about how there’s always someone worse off than you. You might have cancer but at least it’s treatable. You might have a colostomy bag, but what about the blind man with the colostomy bag (another of my stoma nurse’s patients)? There’s always someone worse off, says Arlo Guthrie, until you get to the last guy. Just think about him for a minute.

I’m typing this with one finger on an iPad, in amongst the kelpies at Larissa’s house. I’ve got to have one last chemo session tomorrow. By 3pm tomorrow, I’ll officially be in remission!

Colostomy chic

Colostomy chic. Who would have thought it was a thing? Well, it is. I have to admit that before I woke up out of an anaesthetic fog with my own, I’d associated the colostomy bag with the old and doddery. Since then, it’s been a sharp learning curve. There’s a world of Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis and all sorts of cancers out there, hitting people of all ages and stages. Some of these are fashionable young women, and they’ve taken to the Internet with their thoughts and hints and tips. Mostly it’s all about how to dress to obscure the outlines of the bag: lots of ruching, ruffles and artful drapery.

There’s also a world of options if you’d like to choose decorative bag covers or a sexy look.

But some have taken colostomy chic a step further, choosing the “out and proud” route to overcoming shame and stigma. Last week, one of the comments on this blog drew my attention to Bethany Townsend, a 23 year old model who posted a photo of herself in a bikini on Facebook. The pic went viral – in a good way. Then there are people like rock-climbing blogger Heidi Skiba who has an ileostomy (where all of the large intestine is removed, not just part of it as in a colostomy). Photos on her blog show off an outdoorsy life in full swing, as well as the occasional pic with her bag in plain view.

It isn’t that long ago that the colostomy bag was one of life’s great unmentionables. But that’s changing rapidly.

Lee, my stoma nurse at Westmead, gave me a rundown on the history of the bag along with practical instructions about how to use the ones she was waving under my nose. She said it was only in the 1950s that colostomy bags became widespread. One of her favourite patients was an older man who’d had surgery as a teenager. There were no colostomy bags available at the time, so his stoma (outlet) was simply wrapped up in dressings, which his mother changed for him. When a rubber colostomy bag became available, his life changed. He became a bank manager and lived “happily ever after” (he recently died of an unrelated problem). Still, it would not have been easy back in the 1950s and ’60s. The community nurse who visited me last week (whose daughter’s boyfriend is working for Angelina Jolie, entertaining her kids – how’s that for three degrees of separation?) said that those old rubber colostomy bags were a bit stinky. Unlike today’s light, waterproof versions with their own little charcoal filters, the old versions didn’t stick to the skin; they were held on by a belt, and the situation was always in danger of becoming iffy. One solution was the use of a black tar-like substance that people used to slather over their stomachs to get a seal. This was messy.

So I’m glad that having had the misfortune of losing a length of my large intestine, I have at least had the good fortune of arriving at a time when colostomy bags are well designed, when the Internet is a portal to “ostomates” around the world and there is such a thing as colostomy chic.

Meanwhile, I continue to feel fabulous. I keep forgetting that I’ve got one last chemo session next week; that I’m not out of the sick-bay yet.

And – just a quick and inadequate thank you to family and friends who just keep on coming with care packages, flowers, cards, soup and – the latest – fun hats and skeins of teal and purple wool!

Yes, you may eat the oysters

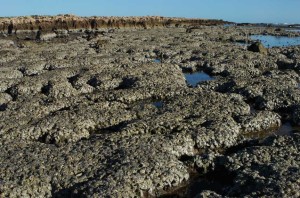

At the Blowholes, a popular fishing and camping spot north of Carnarvon in WA, there’s a sign that says: “Yes, you may eat the oysters.” I’m assuming it’s still there – it was in 2005 when I took Steve to see one of my favourite places on the planet. At first it looked like one of those signs that give you a great big list of things you can’t do. But this one just said go for it, and gave hints and tips. Prise the shell open with a bread knife. Swish the oyster round in the sea to rinse it. Chew and swallow it, savouring the blast of pure ocean feeling. Or something along those lines.

Today I’m thinking about oysters and impermanence. Last week, it was a year since Dad “went”. I like that euphemism. He went somewhere, not sure where, but the fact is that he is gone and isn’t coming back. Not the way we knew him. I think of his arm muscles. He used to pump them up to show them off. The blood coursing through those veins. The tattoo on his bicep with the pink love-heart and the word “Yvonne” in a scroll across it. Just before he went, I looked at that tattoo, so familiar all my life, and noticed that it was hanging on loose skin and you could no longer really tell what it was. That was once the strong arm that changed tyres, drove trucks, prised oysters out of their shells from the rocks.

Nothing (nothing that we definitely know about) is permanent. Everything is coming and going, coming and going, coming back in different form, from a living body to ash to a living body again. There is no permanence, but there can be repetition.* You can’t go back to how it was, but you can do things again. It won’t be like the last time but it’ll remind you of the last time. You can eat oysters again. That’s what we did last Wednesday when, in honour of Dad, we bought a towering stack of seafood at the Shelly Beach golf club, with a view out over the sea, this time the Pacific. Most of the seafood, I’m sorry to say, was pretty ordinary. There is nothing like growing up on the coast of WA to spoil you forever for fresh prawns and lobsters (we called them crayfish or crays). But the fresh oysters, served in their shells, were plump and the taste was not nostalgic but thrillingly right-now. The oysters of now!

I can’t go back and eat the oysters of then. But I can eat the oysters of now. Dad is, all at once, a boy and a man and some ashes floating in Moreton Bay between the mainland and Stradbroke Island.

We’re all coming and going. We’re the bored child at the bed of the ailing relative, and we’re the ailing relative. We’re leaping through a sprinkler and we’re painfully making our way down a hospital corridor, drip-stand in tow, heading for the light coming through the window.

Just after my surgery in May, my friend Jacquie brought in a book of quotes by Jack Kerouac called You’re a Genius All The Time. After she’d left, I sat in bed and read:

No fear or shame in the dignity of your experience, language & knowledge

We’re all coming and going, all the time. Death is the primary fact of life; it’s there in life’s first breath. And yet there’s this fear and shame. Being diagnosed with Stage 3 cancer has sometimes felt shameful, even though I tell myself there’s no shame in it. I’m somehow failing, not doing life right, by growing tumours in my abdomen. And yet this is ridiculous. Everybody dies; everyone who has ever lived has died or will die. There is no shame in growing tumours or having tuberculosis or a stroke or a heart attack. These are simply different forms taken by the great, inevitable, unavoidable fact of life.

Reading that sentence from Kerouac, I sat in bed sobbing, but in a good way. The young nurse got interested. “Who is Jack Kerouac? I’ve never heard of him.”

“He wrote a book called On the Road.” I think she thought Kerouac was some sort of self-help author.

“What does he say?”

I read out the sentence, sobbing through it again.

“That’s true,” she said.

Today, I feel good and most excellently alive. All my numbers and scans are excellent. My tumours have been taken out. The doctors are impressed with my progress. I have only one more chemo session before the end of all this treatment and surgery. After that, I can look forward to feeling well in Spring. And then I can look forward to a nice long remission. Let’s say twenty years – why not? Every now and then, during that time, I’ll eat oysters.

* Repetition is the only form of permanence that Nature can achieve.